4th November 2018

Whisky Production: Mashing and Fermentation

Whisky is made by distilling beer. As such, we first need to produce a beer before we can distil it. This article covers the brewing process for whisky.

Having converted the starch in the barley to fermentable sugars by malting, we now want to extract the sugar. The yeast can then be added in order to produce the alcoholic liquid that will later become whisky.

Brewing is separated into two distinct stages:

- Mashing: also known as the hot side. This is where the malted barley is mixed with hot water to dissolve the sugars.

- Fermentation: also known as the cold side. Yeast is added to the sugary liquid (called wort) to produce alcohol.

Milling: Preparing the malt for brewing

In order to make the sugar accessible for brewing, the malt must be broken up into grist.

In order to make the sugar accessible for brewing, the malt must be broken up into grist.

The malt first passes through a dresser to remove stones and other larger objects. A magnet also stops any metal objects from reaching the mill and causing damage. There are a variety of mill types in use but by far the most popular use two sets of rollers. The first set cracks open the husk while the second set shreds the grain.

The milled malt can be classified into three categories based on size: husks; grit; flour. The flour allows for the best extraction of sugars but using too much can quickly clog the mash tun. For this reason husk is also added to help with filtration. The mill is calibrated to achieve a certain ratio of grit:husks:flour, usually around 70:20:10.

The two mills most commonly used in the whisky industry are those manufactured by Porteus and Robert Boby. These mills were made to be so efficient that they rarely needed servicing. In fact they were so good that they never had to be replaced, forcing the producers out of business when they couldn’t secure any repeat custom.

Mashing: Extracting the sugars

Once the malt has been milled, it is mixed with hot water to extract the sugars and any remaining starch. This stage is known as mashing.

The milled malt is initially mixed with water at a temperature of around 64°C. During mashing the grist absorbs water and the sugars begin to dissolve. The remaining starch gelatinises in the hot water, making it easier for the enzymes to hydrolyse it further into fermentable sugars. The first water is then drained off and a second water is added at a temperature of around 70°C. The higher temperature of the second water dissolves further sugars, increasing the extract efficiency. This water is again drained off and a third water is added at temperatures between 80°C and 90°C. The third water ensures that as much sugar as possible is extracted from the mash. The sugar content in the third water is so low however, that it is not used in fermentation but instead recycled and used as the first water for the next mash. Depending on the distillery, occasionally a fourth water is also used.

There are three types of vessels in which mashing can take place: mash, lauter and semi-lauter tuns. Traditional mash tuns use large paddles to mix the grain whereas lauter tuns use a series of revolving rakes. Lauter tuns are thereby able to agitate and apply pressure to the mash to a higher degree, increasing extraction efficiency. All other designs between mash and lauter tuns are categorised as semi-lauter tuns. All three have slots in the floor to filter off the sugary liquid, now called wort.

Once mashing is completed, the remaining grain (called spent grains or draff) is removed from the mash tun. It is often sold on to farmers to be used as cattle feed due to its nutritional value. The wort now moves to the fermentation tanks, or washbacks, for the next stage: fermentation.

Fermentation: Converting the sugars into alcohol

Yeast convert sugars to alcohol and carbon dioxide, as well as a number of additional compounds. These include esters, fusels, sulphur and carbonyls, many of which will lend specific aromas and flavours to the finished whisky. As such, the fermentation stage, including which yeast strain is selected, has a large impact on the characteristics and quality of the final product. Distiller’s yeasts are bred to survive the high sugar concentrations of the wort and produce desirable flavour compounds.

Yeast convert sugars to alcohol and carbon dioxide, as well as a number of additional compounds. These include esters, fusels, sulphur and carbonyls, many of which will lend specific aromas and flavours to the finished whisky. As such, the fermentation stage, including which yeast strain is selected, has a large impact on the characteristics and quality of the final product. Distiller’s yeasts are bred to survive the high sugar concentrations of the wort and produce desirable flavour compounds.

The yeast is added to the wort in a large vessel (up to 30,000 litres) known as a washback. These were traditionally made from Oregon pine, although steel is becoming more popular for its ease of cleaning. Many people within the industry swear that the wooden washbacks lend a flavour to the whisky that steel cannot replicate. Distilleries that use steel claim however that tests on both types of washbacks show no significant difference in flavour.

After pitching there is an initial lag phase when the yeast acclimatises to its new environment. During this time the yeast begin absorbing nutrients from the wort and producing the enzymes necessary for growth. The yeast then begin to consume sugar and produce alcohol, growing exponentially. As already mentioned the yeast also produce carbon dioxide. This causes the wort to foam and can lead to the washbacks overflowing. Many washbacks have rotating blades above the wort to cut the foam and prevent this from happening. The process also produces heat, raising the temperature of the wort from about 20°C to roughly 32°C. This heat increase must be kept in check as excessive temperatures can exert stress on the yeast and negatively affect the fermentation.

Once the nutrients and sugars in the wort have been exhausted, the yeast activity begins to decline. The length of the fermentation process varies between distilleries but is commonly between 48 and 100 hours. The alcoholic liquid, now called wash and very similar to an un-hopped beer, is transferred to the stillhouse for the next stage in whisky production: Distillation.

Want to learn more about whisky production?

Take a look at the next step in the production process: Distillation

You might also like:

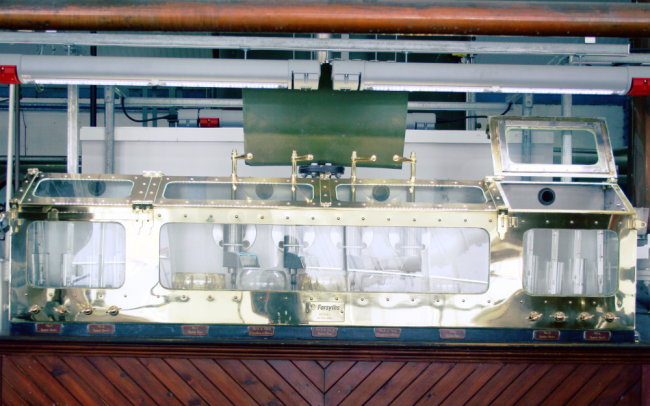

The stills in which single malt Scotch whisky is produced are, by law, made from copper. They consist of a large pot base with a tall, thin neck (known as a “swan neck”), which ends in an angled turn into a pipe called a lyne arm. This pipe is connected to a condenser which will cool the vapours coming off the still back into liquid form. The liquid coming off the stills then flows through a receiving vessel called a spirit safe. This is a locked glass box where the stillman can check the spirit and decide when to start collecting the liquid that will become whisky. The spirit safe is kept locked by the local excise official to prevent alcohol from being siphoned off before it can be measured for tax purposes. The first still, into which the wash is filled, is called the wash still. When heated, the ethanol, as well as various compounds, will begin to vaporise and rise in the still. Much of the vapour will condense on the sides of the still and fall back into the pot. This reflux ensures that only the lighter, desirable compounds reach the top of the still. The copper in the stills also helps to strip away the heavier compounds, such as sulphur, ensuring a lighter spirit. Once the vapour has made it around the head and into the lyne arm, it reaches the condensors. Here cold water flows along the sides of the pipes to cool the vapour back into liquid form. The liquid, now called low wines passes through the spirit safe and is collected in the low wines receiver. The liquid coming off the still first is higher in alcohol (roughly 45% ABV); as the distillation progresses the alcohol content falls. When the alcohol content of the low wines coming off the still reaches around 1% the distillation is deemed complete. The collected low wines will have be approximately 25% ABV. The second distillation takes place in the spirit still. It is similar to the first, however the resulting liquid is separated into three “cuts”: heads, hearts and tails. The heads, also called foreshots, are the first runnings of the spirit still. They contain all of the lighter compounds that vaporise first, including volatile and aromatic compounds such as ethyl acetate. These are not deemed worthy of collection and are rerouted via the spirit safe back to the low wines receiver. They will be distilled again with the next batch. After approximately 10 – 30 minutes, once the alcohol content has fallen to roughly 75% ABV, the stillman will turn a handle in the spirit safe and begin collecting the hearts. The hearts, also called the middle cut, contain all of the desirable flavours and aroma compounds. This liquid will be collected in the spirit receiver and will later, after maturation, become whisky. For now though it is called new make spirit. The choice of when to begin and stop collecting the hearts has a major impact on the level of compounds in the final spirit. Therefore this decision has a significant effect on the final character and is a major contributor to the differences between whiskies from separate distilleries. Another contributing factor to the differences between distilleries is the shape of the still and the angle of the lyne arm. Shape and height both influence the level of copper contact and reflux. Taller stills with upward reaching lyne arms generally result in lighter whiskies. Collection of the new spirit lasts roughly 3 hours, when the alcohol content falls to roughly 60% ABV, before the tails begin to run off the still. The tails, also called the feints, contain all of the heavier compounds, such as fusel oils, that are not desirable in the spirit. The stillman will again turn the handle on the spirit safe and redirect the tails to the low wines receiver. Again these will be distilled in the next run. The collected new make will now be transferred to casks for maturation. Take a look at the next step in the production process: Maturation and Bottling.

The stills in which single malt Scotch whisky is produced are, by law, made from copper. They consist of a large pot base with a tall, thin neck (known as a “swan neck”), which ends in an angled turn into a pipe called a lyne arm. This pipe is connected to a condenser which will cool the vapours coming off the still back into liquid form. The liquid coming off the stills then flows through a receiving vessel called a spirit safe. This is a locked glass box where the stillman can check the spirit and decide when to start collecting the liquid that will become whisky. The spirit safe is kept locked by the local excise official to prevent alcohol from being siphoned off before it can be measured for tax purposes. The first still, into which the wash is filled, is called the wash still. When heated, the ethanol, as well as various compounds, will begin to vaporise and rise in the still. Much of the vapour will condense on the sides of the still and fall back into the pot. This reflux ensures that only the lighter, desirable compounds reach the top of the still. The copper in the stills also helps to strip away the heavier compounds, such as sulphur, ensuring a lighter spirit. Once the vapour has made it around the head and into the lyne arm, it reaches the condensors. Here cold water flows along the sides of the pipes to cool the vapour back into liquid form. The liquid, now called low wines passes through the spirit safe and is collected in the low wines receiver. The liquid coming off the still first is higher in alcohol (roughly 45% ABV); as the distillation progresses the alcohol content falls. When the alcohol content of the low wines coming off the still reaches around 1% the distillation is deemed complete. The collected low wines will have be approximately 25% ABV. The second distillation takes place in the spirit still. It is similar to the first, however the resulting liquid is separated into three “cuts”: heads, hearts and tails. The heads, also called foreshots, are the first runnings of the spirit still. They contain all of the lighter compounds that vaporise first, including volatile and aromatic compounds such as ethyl acetate. These are not deemed worthy of collection and are rerouted via the spirit safe back to the low wines receiver. They will be distilled again with the next batch. After approximately 10 – 30 minutes, once the alcohol content has fallen to roughly 75% ABV, the stillman will turn a handle in the spirit safe and begin collecting the hearts. The hearts, also called the middle cut, contain all of the desirable flavours and aroma compounds. This liquid will be collected in the spirit receiver and will later, after maturation, become whisky. For now though it is called new make spirit. The choice of when to begin and stop collecting the hearts has a major impact on the level of compounds in the final spirit. Therefore this decision has a significant effect on the final character and is a major contributor to the differences between whiskies from separate distilleries. Another contributing factor to the differences between distilleries is the shape of the still and the angle of the lyne arm. Shape and height both influence the level of copper contact and reflux. Taller stills with upward reaching lyne arms generally result in lighter whiskies. Collection of the new spirit lasts roughly 3 hours, when the alcohol content falls to roughly 60% ABV, before the tails begin to run off the still. The tails, also called the feints, contain all of the heavier compounds, such as fusel oils, that are not desirable in the spirit. The stillman will again turn the handle on the spirit safe and redirect the tails to the low wines receiver. Again these will be distilled in the next run. The collected new make will now be transferred to casks for maturation. Take a look at the next step in the production process: Maturation and Bottling.

- produced entirely in Scotland;

- that has been distilled at an alcoholic strength by volume of less than 94.8 per cent so that the distillate has an aroma and taste derived from the raw materials used in its production;

- that has been matured entirely in an excise warehouse or a permitted place in Scotland in oak casks of a capacity not exceeding 700 litres for a period of not less than three years;

- to which no substance has been added except water and/or plain caramel colouring; and

- that is bottled at a minimum alcoholic strength by volume of 40%.