5th May 2019

Visiting Islay: Queen of the Hebrides and Whisky’s Crown Jewels

Islay is the fifth-largest of the Scottish Isles and is the most southerly of the inner Hebrides. During the 13th to 15th centuries it acted as the seat of the Lord of the Isles before John MacDonald II had his ancestral homeland, estates, and titles seized by King James IV of Scotland.

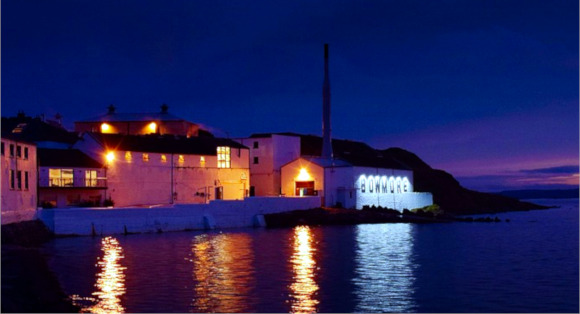

The capital, Bowmore, is located at the heart of the island on the shore of Loch Indaal. In the 19th century the population of the island was around 18,000, in the present day that number has shrunk to a little over 3,000.

Distilleries

Of course, one of the main reasons for visiting Islay is to enjoy its world-renowned whiskies – and if you’re on this site, that’s probably your intention. Islay currently boasts a total of eight distilleries, although the imminent opening of Ardnahoe and the reopening of Port Ellen (mothballed since 1983) next year will soon push that number to ten.

Of course, one of the main reasons for visiting Islay is to enjoy its world-renowned whiskies – and if you’re on this site, that’s probably your intention. Islay currently boasts a total of eight distilleries, although the imminent opening of Ardnahoe and the reopening of Port Ellen (mothballed since 1983) next year will soon push that number to ten.

Each of the distilleries offer a selection of tours, from the basic walkthrough of the production process to a special warehouse tasting with samples drawn directly from the casks. Booking in advance is highly recommended as spaces are limited.

Further information (including available tours) can be found at each of the distilleries’ websites:

- Ardbeg – https://www.ardbeg.com/

- Ardnahoe – https://ardnahoedistillery.com/

- Bowmore – http://www.bowmore.com/

- Bruichladdich – https://www.bruichladdich.com/

- Bunnahabhain – https://bunnahabhain.com/

- Caol Ila – https://www.malts.com/en-row/distilleries/caol-ila/

- Kilchoman – https://kilchomandistillery.com/

- Lagavulin – https://www.malts.com/en-row/distilleries/lagavulin/

- Laphroaig – https://www.laphroaig.com/

Getting there

By sea

There are two main ports on the island – Port Ellen and Port Askaig. Regular ferry crossings operate from Kennacraig on the Kintyre Peninsula, which is roughly a two-hour drive from Glasgow. A bus service by SCOTRAIL also connects Glasgow Central Station and the ferry terminal, although the service is rather infrequent.

Foot passenger tickets can generally be purchased at the terminal on the day of travel, however in the summer months advanced booking is recommended. Passengers wishing to travel with a vehicle will need to book in advance.

Further information can be found on the ferry service’s website – https://www.calmac.co.uk/

By air

Loganair operate flights from Glasgow directly to Islay. The flight takes only 40 minutes, giving you more time in the visitors centre of your favourite distillery. Nevertheless, proceed with caution – I have heard many stories of flights being cancelled; Islay’s airport is directly on the coast, the runway in notoriously short and the weather often unaccommodating.

Getting around

There is a frequent bus service on the island that stops at all the main points of interest. Further information and the current timetable can be found here – https://www.argyll-bute.gov.uk/isle-islay-portnahavenport-askaig-bowmore-port-ellen-ardbeg.

There are also several taxi companies operating which can be useful to get to the harder to reach destinations – Kilchoman for example.

For those who prefer to be more independent in their travel plans, there is a car hire company at the airport (https://www.islaycarhire.com/). Of course, this may not be the best option if your primary objective is visiting distilleries – the tastings provided after the tours will put you over the legal limit, please do not drink and drive.

Honestly, given the size and natural beauty of the island, the best way to get around is to simply strap on your hiking boots and discover Islay on foot.

Where to stay

There are several hotels on the island, however during the busy season these fill quickly. Private rentals are usually the best way to go, with sites such as Airbnb offering anything from single rooms in a shared house to entire properties with outstanding views.

Visitors with motorhomes will find facilities behind the petrol station in Port Ellen, as well as camping spots at Kintra Farm and Port Mor. The road between Bridgend and Bruichladdich offers scenic views over Loch Indaal and can be a lovely (albeit unofficial) place to park up for the night.

Bowmore offers a central location and lies directly on the main bus route, making the rest of the island easily accessible. Amenities in the town are good, with a selection of restaurants as well as a supermarket. Alternatively, Port Ellen also offers good amenities, is easily located for the ferry and can make a good base, especially for those wishing to walk the three-distillery path.

Things to do

The Three Distilleries Path

The Three Distilleries Path

The three distilleries path runs from Port Ellen over Laphroaig, Lagavulin and finally on to Ardbeg. With 3 of the island’s most well-known distilleries along a 3-mile stretch, it is a popular route for whisky-enthusiasts looking to tick off as many distilleries as possible.

If booked in advance, it is possible to tour all three distilleries in one day. However, the more ‘advanced’ tours come highly recommended and include more exclusive experiences, such as warehouse tastings. If you run out of time for a full tour, each of the distilleries offers the opportunity to try a selection of their whiskies in the bar.

Islay Woolen Mill

This family owned business sits on the main Port Askaig road near Bridgend and produces wool using a traditional method on two Dobcross looms. Wools produced by the mill have been used in various Hollywood movies, including Braveheart. Although no official tour is offered, the owners are usually happy enough to show interested visitors around.

Museum of Islay Life

Located in Port Charlotte, the Museum of Islay Life houses a large and fascinating collection of artefacts, including books, clothes and photographs, all with the objective of displaying and preserving items representative of life in Islay over the past 12,000 years.

Finlaggan

Now nothing more than a ruin, Finlaggan was the seat of the Lords of the Isles and of Clan Donald during the 13th to 15th centuries and served as the administrative centre for the Hebrides. The site is now maintained by the Finlaggan Trust and the museum, situated in a refurbished cottage next to the loch, contains a number of artefacts that depict the history of the castle and the Lords of the Isles.

Beaches

Islay has some beautiful beaches to offer. Crystal blue waters and fine white sand can be found at Machir Bay on the west coast of the island. Alternatively, a walk along the beach at Port Ellen will bring you right up to the old Port Ellen distillery warehouses.

Portnahaven

Portnahaven is a picturesque little village with white-washed houses and is located directly on a bay on the southern tip of the Rhinns (Islay’s western half). The bay itself is the perfect place for spotting grey seals which often sunbathe on the rocks and the view is the perfect backdrop for a lunchtime picnic. Alternatively, the An Tigh Seinnse Pub serves brilliant food.

Just off the coast from the village, on the small island of Orsay, is the Rhinns lighthouse. Built in 1825 by Robert Stevenson, the light was ingeniously designed to provide constant illumination with a bright flash every 12 seconds.

Sea Safari

Back in the day whisky would have left the distilleries by boat; ingredients were delivered to and casks would have been taken directly from the distillery’s pier. With a boat trip from Port Ellen it is possible to get a unique view of the distilleries and gain an idea of how intrinsic the sea was to Islay’s whisky industry.

Additionally, you will be able to visit Islay’s Special Area of Conservation which is only viewable from the sea. Here you will see grey seals, red deer, a variety of birds and occasionally dolphins.

Golf

Golf probably isn’t one of the first things that comes to mind when someone mentions Islay but it is home to one of the world’s top 100 courses, the Machrie. A 6,524-yard-long links course awaits golfers who play the Machrie and includes some breath-taking views along the coast.

Islay Festival – Feis Ile

In the last week of May, Feis Ile celebrates everything about Islay’s culture and heritage. From traditional music, ceilidhs, poetry, Gaelic lessons, golf, and whisky tasting, there is something for everyone.

Of course, the distilleries also have open days during the week and special bottlings for the festival are released.

Further information

Peat Smoke & Spirit (Andrew Jefford) – One of my favourite books. It covers the history and landscape of Islay and contains chapters on each of the island’s distilleries.

Islay Info – Tourist information website – https://www.islayinfo.com/

You might also like:

- produced entirely in Scotland;

- that has been distilled at an alcoholic strength by volume of less than 94.8 per cent so that the distillate has an aroma and taste derived from the raw materials used in its production;

- that has been matured entirely in an excise warehouse or a permitted place in Scotland in oak casks of a capacity not exceeding 700 litres for a period of not less than three years;

- to which no substance has been added except water and/or plain caramel colouring; and

- that is bottled at a minimum alcoholic strength by volume of 40%.

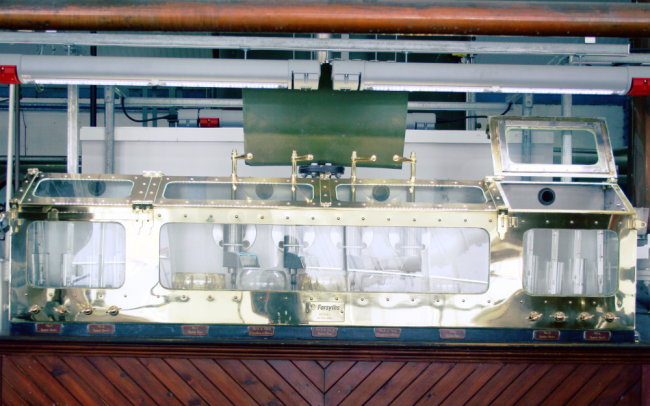

The stills in which single malt Scotch whisky is produced are, by law, made from copper. They consist of a large pot base with a tall, thin neck (known as a “swan neck”), which ends in an angled turn into a pipe called a lyne arm. This pipe is connected to a condenser which will cool the vapours coming off the still back into liquid form. The liquid coming off the stills then flows through a receiving vessel called a spirit safe. This is a locked glass box where the stillman can check the spirit and decide when to start collecting the liquid that will become whisky. The spirit safe is kept locked by the local excise official to prevent alcohol from being siphoned off before it can be measured for tax purposes. The first still, into which the wash is filled, is called the wash still. When heated, the ethanol, as well as various compounds, will begin to vaporise and rise in the still. Much of the vapour will condense on the sides of the still and fall back into the pot. This reflux ensures that only the lighter, desirable compounds reach the top of the still. The copper in the stills also helps to strip away the heavier compounds, such as sulphur, ensuring a lighter spirit. Once the vapour has made it around the head and into the lyne arm, it reaches the condensors. Here cold water flows along the sides of the pipes to cool the vapour back into liquid form. The liquid, now called low wines passes through the spirit safe and is collected in the low wines receiver. The liquid coming off the still first is higher in alcohol (roughly 45% ABV); as the distillation progresses the alcohol content falls. When the alcohol content of the low wines coming off the still reaches around 1% the distillation is deemed complete. The collected low wines will have be approximately 25% ABV. The second distillation takes place in the spirit still. It is similar to the first, however the resulting liquid is separated into three “cuts”: heads, hearts and tails. The heads, also called foreshots, are the first runnings of the spirit still. They contain all of the lighter compounds that vaporise first, including volatile and aromatic compounds such as ethyl acetate. These are not deemed worthy of collection and are rerouted via the spirit safe back to the low wines receiver. They will be distilled again with the next batch. After approximately 10 – 30 minutes, once the alcohol content has fallen to roughly 75% ABV, the stillman will turn a handle in the spirit safe and begin collecting the hearts. The hearts, also called the middle cut, contain all of the desirable flavours and aroma compounds. This liquid will be collected in the spirit receiver and will later, after maturation, become whisky. For now though it is called new make spirit. The choice of when to begin and stop collecting the hearts has a major impact on the level of compounds in the final spirit. Therefore this decision has a significant effect on the final character and is a major contributor to the differences between whiskies from separate distilleries. Another contributing factor to the differences between distilleries is the shape of the still and the angle of the lyne arm. Shape and height both influence the level of copper contact and reflux. Taller stills with upward reaching lyne arms generally result in lighter whiskies. Collection of the new spirit lasts roughly 3 hours, when the alcohol content falls to roughly 60% ABV, before the tails begin to run off the still. The tails, also called the feints, contain all of the heavier compounds, such as fusel oils, that are not desirable in the spirit. The stillman will again turn the handle on the spirit safe and redirect the tails to the low wines receiver. Again these will be distilled in the next run. The collected new make will now be transferred to casks for maturation. Take a look at the next step in the production process: Maturation and Bottling.

The stills in which single malt Scotch whisky is produced are, by law, made from copper. They consist of a large pot base with a tall, thin neck (known as a “swan neck”), which ends in an angled turn into a pipe called a lyne arm. This pipe is connected to a condenser which will cool the vapours coming off the still back into liquid form. The liquid coming off the stills then flows through a receiving vessel called a spirit safe. This is a locked glass box where the stillman can check the spirit and decide when to start collecting the liquid that will become whisky. The spirit safe is kept locked by the local excise official to prevent alcohol from being siphoned off before it can be measured for tax purposes. The first still, into which the wash is filled, is called the wash still. When heated, the ethanol, as well as various compounds, will begin to vaporise and rise in the still. Much of the vapour will condense on the sides of the still and fall back into the pot. This reflux ensures that only the lighter, desirable compounds reach the top of the still. The copper in the stills also helps to strip away the heavier compounds, such as sulphur, ensuring a lighter spirit. Once the vapour has made it around the head and into the lyne arm, it reaches the condensors. Here cold water flows along the sides of the pipes to cool the vapour back into liquid form. The liquid, now called low wines passes through the spirit safe and is collected in the low wines receiver. The liquid coming off the still first is higher in alcohol (roughly 45% ABV); as the distillation progresses the alcohol content falls. When the alcohol content of the low wines coming off the still reaches around 1% the distillation is deemed complete. The collected low wines will have be approximately 25% ABV. The second distillation takes place in the spirit still. It is similar to the first, however the resulting liquid is separated into three “cuts”: heads, hearts and tails. The heads, also called foreshots, are the first runnings of the spirit still. They contain all of the lighter compounds that vaporise first, including volatile and aromatic compounds such as ethyl acetate. These are not deemed worthy of collection and are rerouted via the spirit safe back to the low wines receiver. They will be distilled again with the next batch. After approximately 10 – 30 minutes, once the alcohol content has fallen to roughly 75% ABV, the stillman will turn a handle in the spirit safe and begin collecting the hearts. The hearts, also called the middle cut, contain all of the desirable flavours and aroma compounds. This liquid will be collected in the spirit receiver and will later, after maturation, become whisky. For now though it is called new make spirit. The choice of when to begin and stop collecting the hearts has a major impact on the level of compounds in the final spirit. Therefore this decision has a significant effect on the final character and is a major contributor to the differences between whiskies from separate distilleries. Another contributing factor to the differences between distilleries is the shape of the still and the angle of the lyne arm. Shape and height both influence the level of copper contact and reflux. Taller stills with upward reaching lyne arms generally result in lighter whiskies. Collection of the new spirit lasts roughly 3 hours, when the alcohol content falls to roughly 60% ABV, before the tails begin to run off the still. The tails, also called the feints, contain all of the heavier compounds, such as fusel oils, that are not desirable in the spirit. The stillman will again turn the handle on the spirit safe and redirect the tails to the low wines receiver. Again these will be distilled in the next run. The collected new make will now be transferred to casks for maturation. Take a look at the next step in the production process: Maturation and Bottling.